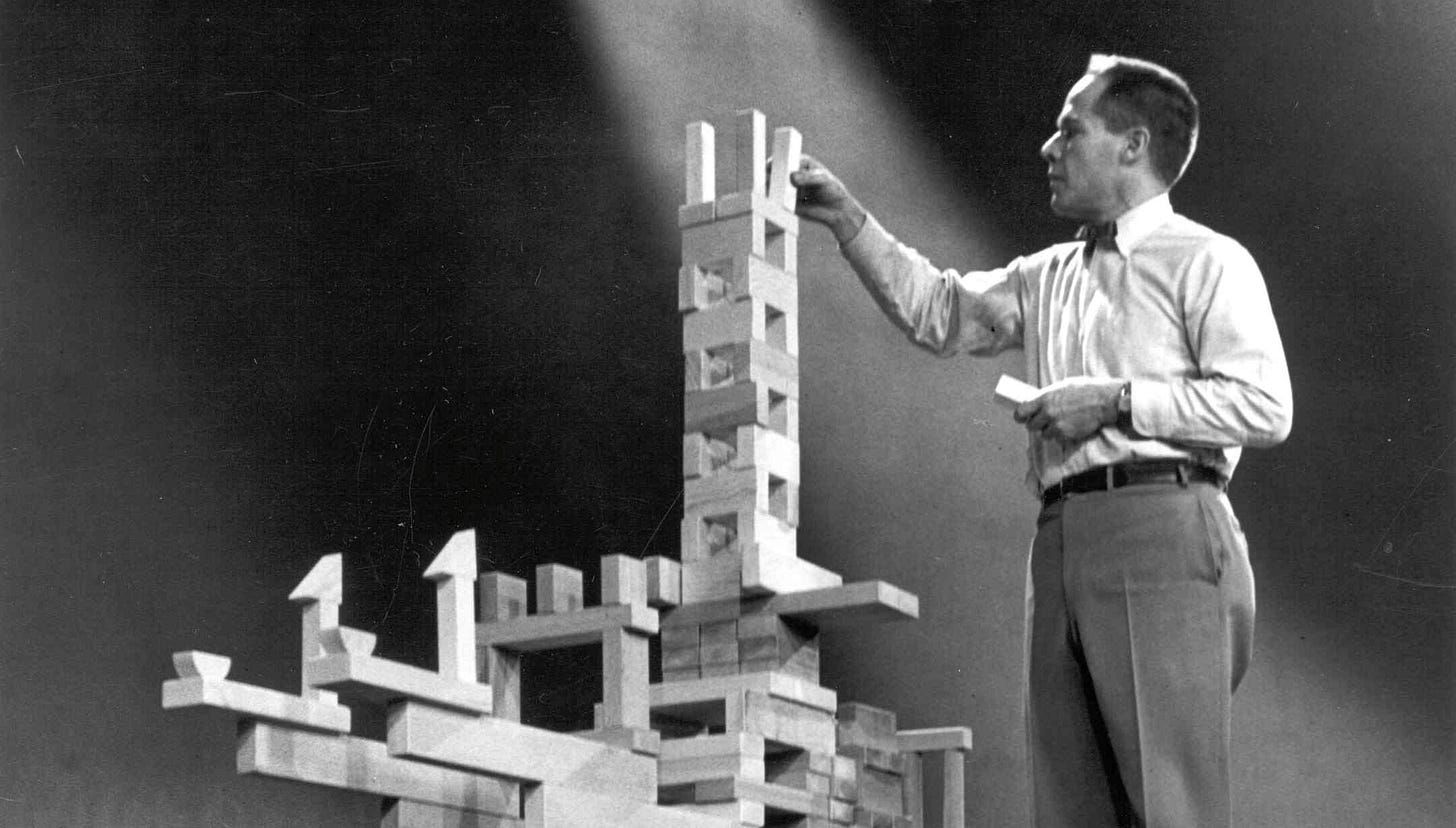

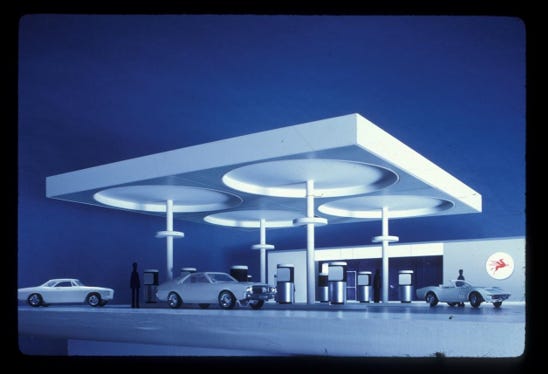

Eliot Noyes is kind-of the design world’s Walt Disney: A brilliant artist in his own right, his actual superpower was envisioning a unified identity for a client, then rallying a team of similarly talented designers to put the plan into action. Noyes’s was the hand that guided IBM to the elemental forms and bold colors of their data processing equipment and the elegant shape of the iconic Selectric typewriter; he was the one that evolved Mobil gas stations from cluttered riots of conflicting visuals to a clean series of circular forms that reflected – as one interviewee notes – the tires and steering wheels of automobiles. Noyes viewed this simplification of visuals as more organic, and his championing of the concept had a lasting impact on the post-war world.

But there was something nagging me about the world being portrayed in Modernism, Inc.: The Eliot Noyes Design Story, and it wasn’t just the specter of Tom Wolfe leaning over my shoulder and cackling wickedly as one of Noyes’ children lovingly describes being obligated to cross, in the middle of the night, the freezing patio of a Noyes-designed home just to use the bathroom. Director Jason Cohn – who previously examined the work of Charles Eames – is justifiably respectful in covering Noyes’s life, but maybe too much so (that IBM partially footed the bill may have something to do with this). The treatment is pretty much talking-head standard, with a few stylistic flourishes, as when the director breaks the screen up into panels of moving images similar to what Charles and Ray Eames did for the Noyes-overseen, IBM film presentation at the '64/'65 New York World’s Fair. And Cohn does manage to give a little due to opposing outlooks, giving us surveys of the genuinely stunning homes Noyes nestled into the woods of places like New Canaan and Martha’s Vineyard, but also noting that some neighbors weren’t especially enamored of the boxy, metal-and-glass structures intruding on nature’s primal beauty.

Left largely unsaid throughout a good portion of the film is how all of this elevated and “progressive” design was concentrated among the thems that gots the money. If you were a person or a corporation of sufficient means, you could dwell in the realm of elevated aesthetics; all others had to make-do with the dregs of cookie-cutter, cheapjack housing (the best Noyes could come up with to address the problem was a proposal to offer low-income houses constructed from concrete-covered balloons. It never got past the prototype stage). That’s underlined in the latter half of the film, when a 1970’s design conference chaired by Noyes is commandeered by a contingent of counterculture designers – including the legendary Ant Farm collective – who proceeded to (loudly) condemn the attendees for their toadying to wealthy clients at the expense of ordinary people and the environment.

Cohn, to his credit, does not lightly brush this protest aside, nor does he caricature its protestors, nor question their sincerity. But in noting the impact the event had on Noyes – the designer resigned his chairmanship and began a slow retreat from active participation in his craft (although a quick survey of his subsequent efforts shows him incorporating more natural building materials into his structures) – the director doesn’t go out of his way to consider that engagement might have been a viable alternative for the shaken designer. That may be too much to ask of a film that’s not meant to be an incisive critique of the blessings and curses of modern design, but rather a celebration of a genuine genius whose impact is felt to this day. (I should note here that that IBM pavilion, and its Thinking Machine, multi-screen presentation, was one of the things that sparked my obsession with entertainment technology and film in general. I can’t outright condemn a man who not only helped make the modern world, but kinda made me as well.) Modernism, Inc.: The Eliot Noyes Design Story is a worthy showcase for an artist not as well-known as his peers, even if it could’ve gone a shade further in evaluating his impact, for good and ill.